Tags

Dovehouse Green is a small patch of public green, situated on the corner of Dovehouse Street and King’s Road, Chelsea. The paths run crosswise from the four corners and where they meet stands an obelisk, known as Millar’s Obelisk.

Dovehouse Green was given to the parish by Sir Hans Sloane to be used as an overspill graveyard. It was consecrated as such in 1736, but by 1812, the new cemetery on Sydney Street had taken over its function and only interments in existing family tombs were allowed. In 1977, the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, the neglected piece of ground was revamped and opened to the public as Dovehouse Green. The centre piece is the obelisk that was originally erected by Andrew Millar, a bookseller, to commemorate his wife and children.

Andrew Millar (1705-1768) came to London from Schotland in the 1720s to work in the bookshop on the Strand that his Edinburgh master James McEuen (or M’Euen) had opened. In January 1728, young Andrew took over the shop, continuing the name, Buchanan’s Head, and starting with the stock that McEuen had had in the shop. But Millar had grander ideas than just selling books and libraries. He became a respected publisher who did his origins proud by publishing, or acting as agent of, a large number of Scottish authors. Samuel Johnson said of him that he was “the Maecenas of the age” who “raised the price of literature”. Unlike most of his competitors, he looked after his authors and gave them bonuses when their books sold well. Was he without fault? No, of course not. Some thought him a bumpkin upstart with unscrupulous tendencies. Perhaps they were just jealous, but perhaps they were right. If nothing else, Millar must at least have been a sharp businessman to get where he ended up as one of the, if not the, most important publisher of the mid-eighteenth century. He was the publisher who took care of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary and his patience must have been sorely tried by the ever-extending time it took to complete. Allegedly when Millar received the last sheet, he sent his compliments with the money due and thanked God he had done with Johnson. To which Johnson replied that he was glad that there was at least something Millar thanked God for.(1)

Mindfull / of Death and of Life

ANDREW MILLAR / of the Strand London Bookseller

Erected This / Near the Dormitory

Intended / For Himself and his Beloved Wife

JANE MILLAR / When it shall please Divine Providence

To call them hence / As a place of Like Rem[embrance]

For other near Relations / and / In Memory of

the deceased Pledges of their love

MDCCLI

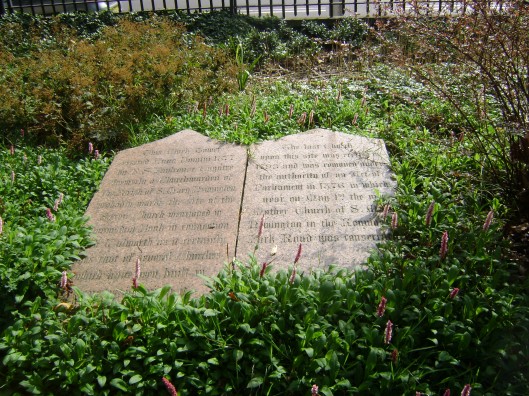

In 1751, Millar had the obelisk erected over the vault where his relations were or would be buried. On the four sides, texts were carved on the pedestal and base to commemorate the family members who were interred, but time has erased most of the inscriptions. On one side, a coat of arms can be seen. And on the other side is still, faintly, visible that the remains of Margaret Johnstone who died in 1757 are buried there. She was Millar’s unmarried sister-in-law who had lived with the family most of her adult life. Although we can no longer read them, we do know what the texts on the other sides originally said. They commemorate the three children of Andrew and Jane Millar who all died young: Robert in 1736, just one year old; Elizabeth in 1740, also one year old; and Andrew junior who died in Scarborough, five years old. The sorrow of the Millar parents is expressed in a poem:(2)

Reader ! if Pity ever touch’d thy Heart

At these sad Lines a tender Thought impart

Think with what Sorrow we inscribe the Stone

That speaks us Parents and that speaks us None.

The bookseller himself died in 1768 and his widow (by then remarried to Sir Archibald Grant) in 1788.

The information on Andrew Millar has come from Richard B. Sher, The Enlightenment & the Book. Scottish Authors & Their Publishers in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Ireland, & America 2006), p. 275-294.

The information on the obelisk has mainly come from “Chelsea Old Town Hall to Knightsbridge”, a publication of Kensington and Chelsea Royal Borough which I can no longer find on their website, but which can still be accessed through Google (online here); and from the Survey of London, Volume 11, Chelsea, Part IV: the Royal Hospital. Originally published by London County Council, London, 1927 (online via British History Online here).

(1) Paul J. Korshin, ‘The mythology of Johnson’s Dictionary‘ in Anniversary Essays on Johnson’s Dictionary, ed. Anne McDermott (2005), p. 16-17.

(2) Samuel Richardson had composed another epitaph on Andrew junior’s death, but Millar chose this one (see here for Richardson’s text).

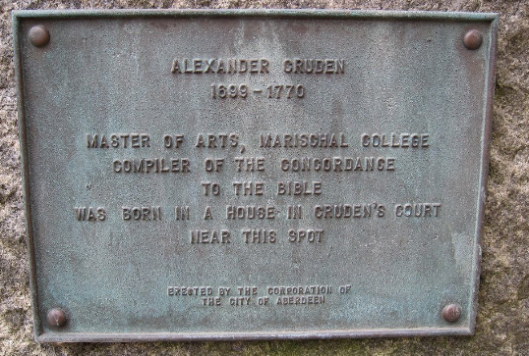

!['Plate 21: No. 58 Davies Street, Boldings', in Survey of London: Volume 40, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings), ed. F H W Sheppard (London, 1980), http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol40/pt2/plate-21 [accessed 26 February 2016].](https://baldwinhamey.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/1890-from-survey.jpg?w=529)